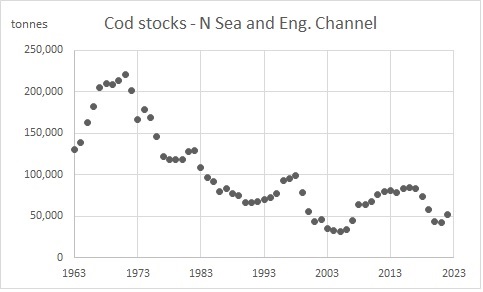

Anglers always seem to be unhappy about fishery rules and management, especially salmon anglers who brood over falling catch returns, worse in recent years.

The majority of British salmon fishermen want two things — fewer rules and more stocking. Trout & Salmon magazine has lately printed two articles along these lines. One by Dani Morey, a Spey guide, is upset about the proposal to introduce compulsory catch and release in Scotland because, she believes, releasing fish is doing nothing to improve stocks; it’s making her ‘blood boil’. This begs the question of what stocks might be like if there had been no catch and releasing. She further undermines her position by pointing out that 95% of salmon are released anyway. What, then, is the big disadvantage of making it 100%?

According to Morey, it is to waste time, just as repeating fishery research wastes time, though she does not expand on the nature of this research. I suspect this is more of a concern for her ghillieing business. Mandatory catch and release may put off a few punters who haven’t got the conservation message. Yet she does have a point about wasting time and futile activities which apparently do nothing to improve salmon populations. Certainly there is little being done to improve salmon stocks, even though we know how to in some cases. Banning open sea cages in aquaculture would be a very good start. Alas, economics trumps the environment, even now.

What else might improve salmon populations? According to the T&S December interview of Bob Kindness (cue corny puns in the byline), liberal stocking from hatcheries is the answer. He runs one on the River Carron on the west coast of Scotland. Naturally this is very popular with anglers and prompted polemics in fishing magazines and online articles. The benefits of hatchery supplements to wild populations have been studied in several long term projects, especially in Ireland and the US. I have seen data that show a stark difference in the behaviour of wild and ranched salmon. The clear conclusion is that indiscriminate stocking adds nothing to wild populations, and may harm them. Only in specific situations using tightly controlled breeding may supplementary stocking help.

Kindness makes bold claims for his work, reminiscent of those of the Avon Roach Project, though stocking a salmon river is potentially more damaging. He cites high survival rate of hatched fish, hardly surprising for tank-reared fish, but offers no figures on the number of hatchery fish that return. He admits they won’t survive at sea as well as wild fish but believes survival in the hatchery tanks more than compensates. It doesn’t: the observed survival rate is 8% that of wild fish. Neither does he understand the concept of biological fitness. Curiously he supports aquaculture which is implicated in reducing salmon and sea trout populations in Scotland and Norway. Like aquaculture, hatcheries use feed derived from marine species, to the overall detriment of wild fish.

Though Kindness is a friend of aquaculture, he is not so well disposed towards the work of scientists on the Atlantic Salmon Trust tracking project, perhaps because scientists have understandably criticised his hatchery work. The AST is one arm of the Missing Salmon Alliance which I’ve previously written about. As I wrote then, the MSA seems little more than a vehicle for waffle. An important factor in salmon numbers is survival at sea but it is a mystery what is happening and where. The AST’s tracking project is an attempt to study smolts as they move downriver and into the open sea; one study looks at the east coast (Moray Firth), one at the west. At least this is something concrete amongst the flannel of the ‘Likely Suspects Framework’ (frameworks seem to be part of the bullshit that infects even science these days). It’s potentially an important project; using some fancy technology it is possible to track smolt progress, at least on the early stages of their journey. Some commentary on progress is on the AST website. In year 1 of the Moray Firth study they appropriately took a ‘positive leap’, finding that half of smolts died while still in the river. They don’t say whether this might be a recent phenomenon or just the way things always have been. Now in year 3 they are looking at the effect of pinch points — man-made obstructions like hydroelectric dams.

The west coast project has not been going so long and there is little to report other than to note that smolts follow many routes northwards. I’m not especially impressed with the progress shown but it is early in the work and perhaps it will yield some important results. More details on the website would be welcome.

More substantial is the research by Dutch scientists in 2016 which I’ve not seen mentioned in any of the fishing magazines (though I don’t buy regular copies). They looked at the Rhine catchment and used historical data on fish prices to infer salmon populations all the way back to the Middle Ages. Their conclusion is that salmon may well have been highly abundant a few hundred years ago but went into decline as water mills and the like were established. An interesting plot compares the UK distribution of salmon with engineering in rivers. The inference is that all the rechannelling of southern rivers centuries back impacted the salmon. It’s a compelling study; the number of lochs, weirs, dams, hydro schemes about now may be a literal barrier to re-establishing good salmon populations, notwithstanding fish passes. There is an interesting coincidence in Thames history. Salmon runs up the river vanished in the early 19th century, which is about when the 45 weirs from St Johns down to Teddington began to be constructed. Teddington was the earliest. No fish passes then. Other factors, particularly pollution, may have done for the salmon, but it fits with the Dutch findings.

What of the future? Persuading landowners to remove their ornamental weirs on my local river is difficult enough. Anglers enthusiastically blame predators — seals, cormorants, otters — and demand more stocking. Habitat and environment restoration will be expensive, especially now it’s been postponed for so many years. Will all those polluting 4x4s anglers are so fond of be given up? Foreign fishing trips too? Do you believe in global warming? I’ve seen the mists of denial drift across so many pairs of eyes. In the meantime there are always hatcheries to trouble wild stocks and guns to shoot cormorants or anything you think you can get away with.